High Stakes

The more observant of you will have noticed that vampires have been in the news. No, not bankers. Although the droll current-affairs metaphor does apply, Voltaire got there first: describing the vampires he had seen in London and Paris in his Dictionaire Philosophique, he wrote

“… there were stock-jobbers, brokers, and men of business, who sucked the blood of the people in broad daylight; but they were not dead, though corrupted. These true suckers lived not in cemeteries, but in very agreeable places.”

Archeologists in Sozopol, Bulgaria have excavated a couple of graves whose inhabitants had been pinned to the ground through their hearts with iron rods. Better safe than sorry, I suppose. Staking is such perfect horror-film fare that it’s hard to believe that it happened in real life too, but it truly did.

Archeologists in Sozopol, Bulgaria have excavated a couple of graves whose inhabitants had been pinned to the ground through their hearts with iron rods. Better safe than sorry, I suppose. Staking is such perfect horror-film fare that it’s hard to believe that it happened in real life too, but it truly did.

Historical Context

Vampires erupted onto Western European consciousness in the early 1700s, but that is not to say they were invented then. The Ottoman Turk and Austrian Empires had been slogging it out for centuries, and when the Austrian Empire finally prevailed in the Balkans, they found themselves administrating over local peoples who had quaint local customs, like mutilating corpses.

A rash of alarmed reports came back, asking how to deal with the phenomenon. To Roman Catholic Austria, desecration of the dead was not just unhygienic – it was sacrilege.

But where there’s repulsion there’s usually titillation too. The response to the new tales of the undead varied, from learned shock and outrage, to ardent and morbid curiosity. Incidentally, this is worth noting for those today who believe “horror” to be a modern and corrupting – pardon the pun – interest.

The Case of Arnod Paole

As early as the first decade of the eighteenth century, the Sorbonne1 in Paris had passed two resolutions prohibiting the decapitation of accused vampires. And Eighteenth century western Europe avidly consumed the vampire stories that streamed in from the east. The case of the vampire Arnod Paole and his numerous victims was one of the first to be seized upon; it was enthusiastically retold, and was the subject of a best selling leaflet at the Leipzig book fair of 1732.

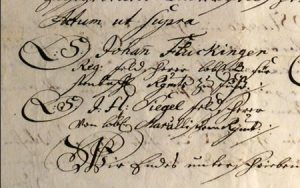

Paole had died when he had fallen from a hay wagon and broken his neck. His case was recounted in Visum et Repertum, a report which had been commissioned by the authorities of the Austrian Empire and written by regimental medical officers Fluckinger, Sigel and Baumgarten.

Paole had died when he had fallen from a hay wagon and broken his neck. His case was recounted in Visum et Repertum, a report which had been commissioned by the authorities of the Austrian Empire and written by regimental medical officers Fluckinger, Sigel and Baumgarten.

Paole had been born and died in the village of Medvegia, north of Belgrade in Serbia, but he had spent part of his life away as a soldier serving in what was then called ‘Turkish Serbia’. After his service, he had returned home, married and bought a farm. Although he was remembered as a pleasant man he was said to have had a sombre air, which was attributed to an incident that he mentioned during his travels; he had claimed to have been troubled by a vampire, and had used the folk remedy of eating earth from its grave and smearing himself in its blood to be free of it.

After his death, some of the villagers said they had been bothered by Paole, and four were reported to have died by his actions. Forty days after his burial, he was disinterred. As Johann Flückinger’s 1732 document, Visum et Repertum, attests, his body was found not to be corrupt:

“They found that he was quite complete and undecayed, and that fresh blood had flowed from his eyes, mouth and ears; that the shirt, the covering of the coffin were completely bloody; that the old nails on his hands and feet, along with the skin had fallen off, and that new ones had grown; and since they saw from this that he was a true vampire, they drove a stake through his heart, according to their custom, whereby he gave an audible groan and bled copiously. Thereupon they burned the body the same day to ashes and threw these into the grave.”

Paole’s four ‘victims’ had also been disinterred and treated the same way since they would be tainted and could turn into vampires themselves. Clearly we have the notion of contagion here.

But the deaths did not stop there. In the three months leading up to the arrival of the medical officers, (five years after Paole’s death) another seventeen people died after short illnesses of two or three days, and one had claimed to have been bothered by the spirit of one of the recently dead before she expired. It was reasoned that the curse of vampirism had managed to persist via the meat of the local cattle and sheep, whose blood Paole must therefore have sucked. The officers were thus able to witness the disinterment of more bodies, as the latest rash of vampires were dealt with.

Paole’s ‘Victims’

A woman named Stana had died at the age of twenty after a three day illness following childbirth. Her baby had not survived for long, and had been buried but then pulled out of its grave by dogs and partially eaten. Stana had been sufficiently worried about the vampire (and had perhaps suspected it for the death of her baby) to smear herself with its blood as a protection against it. But to judge by her pristine condition in the grave three months after her death, this measure had not been effective. Liquid, rather than coagulated, blood was found in her vessels, her viscera were fresh and her nails on one hand were new. The only part of her which had succumbed to the grave was her uterus, inflamed and malodorous with the placenta still in place (giving an indication what why she actually died).

Another woman named Ruscha had been buried with her child soon after parturition. Six weeks and five weeks later respectively, the mother and the baby both had fresh blood in their thoracic cavities and hearts.

An old woman named Miliza had died at the age of sixty, around three months previously. Having spent her whole life looking lean and spare, she now conversely appeared to be plump and healthy in death. Like the others, her blood was liquid and her viscera were fresh.

A twenty year old woman who had been dead for over two weeks was found to be fresh with a flushed and ruddy complexion. When she was moved, fresh blood flowed from her nose.

In total, all the people above plus two teenage boys, one pre-pubescent girl, a woman, a man, a baby and an old man were found in a vampiric state.

All the vampires’ heads were severed from their bodies, the carcasses were burnt and the ashes were thrown into the river Morava. Two mothers and their babies, and a man in his twenties were also exhumed but had decomposed sufficiently to allay suspicion. They were replaced back in the ground without further desecration.

So … Vampires?

Paole’s case illustrates perfectly that vampires were a phenomenon associated principally with two things: epidemics, and failure to decompose in the predicted manner.

The 17th century Greek Roman Catholic Priest Leone Allaci wrote:

“If at any time an unwonted mortality occurs and persons begin to die when there is no epidemic of sickness to account for it, the citizens shrewdly suspecting what the cause may be, proceed to open the graves of those who have been recently interred.”

Ernest Jones2 provided a list of some of the most alarming outbreaks of vampirism: in Chios 1708; Hungary 1726; Medyuega and Belgrade 1725; Serbia 1825; Hungary 1832. These coincided with fatal epidemics – plagues.

A recently as 1898, people on the Island of Kynthos believed that vrykolakas – Greek vampires – brought consumption. Regional variants, such as the Bosnian lampir, were associated with plagues and the Greek word ‘Nosopheros’ (from where the Balkan word Nosferatu derives) means plague carrier.

In a very peculiar twist, Balkan/Greek type folkoric practice in response to consumption also occurred in late nineteenth century Rhode Island, USA. Go here for my vodcast on The Vampires of Rhode Island.

Pristine in the Grave

As for the ‘undecomposed’ element of Paole and his victims, we can fruitfully turn to the science of decomposition – a science to which most people throughout history have not had access. It’s worth starting with an account by a travelling French Botanist, Pitton de Tournefort from his Relation d’un Voyage du Levant of 1717, who had the opportunity of seeing a vampire examined on the Island of Mykonos in 1700.

A quarrelsome and unpleasant man had been found dead in a field, and buried as normal. Two days after his burial, he was seen striding around the town at night. He entered houses and made a great nuisance of himself, upsetting furniture and extinguishing lights. Like many other ‘vrykolalas’ – Greek vampires – he did not suck blood directly, but he terrified the wits out of the living.

Masses were said, but since the disturbances did not stop and were so widespread, that it was decided to exhume his corpse on the ninth day after burial. De Tournefort witnessed the examination which was carried out by the town’s butcher whom he described as “old and ham-fisted”. The butcher’s aim was to find the heart of the vrykolakas, for which he began a search in its abdomen. After a time spent sorting through the corpse’s entrails, it was suggested that he needed to breach the diaphragm to enter the thorax, after which the corpse’s heart was successfully extracted.

Unfortunately by now the stench was overwhelming. Incense was burnt, but the pungent fumes mingled with those of the corpse and the onlookers became so excited that they swore the palls of smoke emanated from the corpse itself. The terror mounted until all de Tournefort could hear was the word ‘vrykolakas’, repeated many times by the people in the Church and in the square outside it. The group who had initially found the man’s corpse in the field added to the hysteria by recounting that when they had found him, he was not as stiff as a corpse should have been, but supple instead.

“I am certain that if we had not ourselves been actually present, these folk would have maintained that there was no stench of corruption” wrote de Tournefort, a stench that meant, having secured a place quite close to the body, “we were retching and well ‘nigh overcome”. The butcher claimed that the innards were warm and that the blood on his hands was fresh; De Tournefort and his associate countered that the warmth was no more than the warmth of putrefaction like that of a dung heap, and that the blood was nothing more than a stinking mess. But despite this reasoning, the people still took the heart to the seashore and burnt it.

Far from being subdued, the spirit became more restless than ever, terrifying everyone except, de Tournefort sardonically adds, “the consul in whose house we lodged”.

It Depends on Your Point of View

De Tournefort believed the whole thing to have been “an epidemical disorder of the brain, as dangerous as mania or sheer lunacy”. Clearly, no amount of reasoning would have convinced the people of Mykenos that there was not a vrykolakas in their midst, but with two parallel interpretations of the same event – the locals’ and De Tournefort’s – we can perceive a cognitive bias which directed people to see putrefying warmth as life, decomposing sludge as blood, and incense as a spirit emanation from a vampire body.

Paul Barber’s excellent Vampires, Burial and Death has a chapter devoted to normal post-mortem changes that can be mistaken for vampirism. I recommend the book. After you’ve eaten.

Stana, Ruscha and her baby, Miliza, the twenty year old woman and Paole himself all had ‘liquid blood’ which in some cases flowed from their noses (and in all likelihood, all other of their bodily orifices).

Barber reminds us that blood coagulates in corpses, but liquefies again. Then, quoting Mant3, he writes:

“The gases in the abdomen increase in pressure as the putrefactive processes advance and the lungs are forced upwards and decomposing blood escapes from the mouth and nostrils”

Stana was round and healthy-looking in the grave, but bloating from post-mortem bacterial gases would account for that, as it would account for the Paole’s “audible groan” as he was staked.

Paole’s twenty year old female victim’s “flushed and ruddy complexion” was quite common in vampirism too. Lividity in corpses occurs where the blood vessels break down, emptying now decaying blood cells into tissue where they can cause dark staining. If a person was suspected of being a candidate for vampirism, they were often buried face-down, which produces significant facial ‘flushing’.

The suppleness of De Tournefort’s vrykolakas was remarked upon by the people who found him. But rigor-mortis passes, usually after thirty six hours or so although the process gets delayed by the cold.

In fact, temperature has a massive part to play in general. As I pointed out with Mercy Brown in The Vampires of Rhode Island, if a person dies and the winter and is buried in freezing soil, buried in a shallow grave because the ground is too hard to dig a deep one, or kept them above-ground in a freezing mortuary, the corpse is not likely to decay particularly rapidly.

Epidemics

Death during epidemics provided another variable which contributed to the revenant myth – the idea that, as French Monk Augustin Calmet put it, “certain persons after death chew in their graves and demolish anything that is near them, and that they can be heard munching like pigs”. This munching occurred especially at times of plague.

I covered this in a previous blogpost. To summarise: the bodily parts that were eaten by ‘vampires’ in their graves were those parts which would decompose first, such as entrails and finger ends. And the phenomenon was most likely to occur in late summer and autumn, the peak season for plague deaths.

While we can look this stuff up on the internet, most people throughout history have not observed the decomposition of corpses for the very good reason that they are sources of contagion. It’s unhygienic.

Our ancestors had nothing but hearsay and folklore to combat epidemic death.

Back to Sozopol

I wonder what happened to the corpses in Sozopol?

We can reasonably infer that the people were likely to have died during a time of plague. Perhaps the village had employed the folk diagnosis used across Southern Slav areas of walking a completely white or black virginal horse that had never stumbled, ridden by a virginal man around the graveyard. The horse would have refused to cross the vampire graves, leading to the corpses being exhumed.

We can reasonably infer that the people were likely to have died during a time of plague. Perhaps the village had employed the folk diagnosis used across Southern Slav areas of walking a completely white or black virginal horse that had never stumbled, ridden by a virginal man around the graveyard. The horse would have refused to cross the vampire graves, leading to the corpses being exhumed.

Staking is an extremely prosaic way of simply keeping a corpse in its grave. It’s a rather large pin. While many traditions emphasise the importance of the material – hawthorn for some, iron for others – piercing the corpse would have let the gases out and stopped post-mortem shifting and popping. Bear in mind that these people did not have coffins and they sometimes had shallow graves.

Scapegoats & Rituals

Vampires, like all other unnatural predators, serve as scapegoats. They provide a way of communities feeling powerful in the face of insurmountable events: there is knowledge, there are rituals. It means that people can do something, where there is otherwise nothing that can be done.

Vampires were officially-designated ‘outsiders’, and it’s observable that such discreet populations within the main one are useful to the human psyche, and oft-created. Given that people have hanged witches, burned heretics and tortured foreigners, perhaps we should applaud the vampire-believers for their humanity in only multilating their scapegoats after they were dead.

Footnotes:

1 The Sorbonne was founded as a theological college – and was not given to University of Paris until 1808

2 Ernest Jones (1949) On the Nightmare The Hogarth Press Ltd, London p. 122.

3 Mant ed. Taylor’s Principles and Practice of Medical Jurisprudence p. 147, quoted in Barber Vampires, Burial and Death p. 115.

First published June 2012