The Battersea Poltergeist, and the role of the paranormal investigator

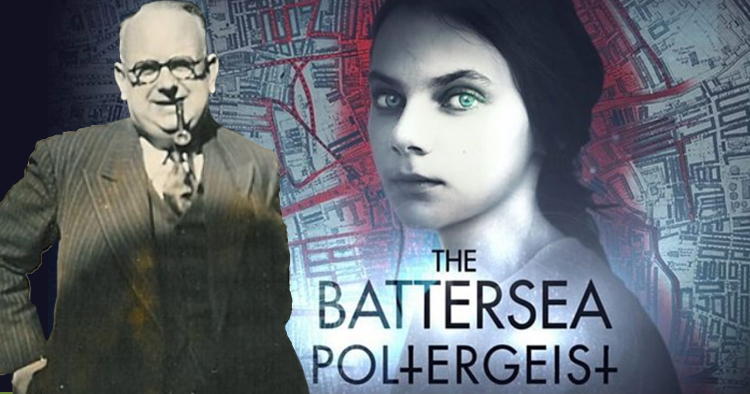

The creation of ghosts, poltergeists and gods is a social enterprise; each supernatural being needs attention to thrive. And the really successful memes are the ones with influential people behind them. Meet Harold Chibbett, the psychic investigator behind the Battersea Poltergeist case.

This article was first published in The Skeptic, May 2021

If you haven’t listened to the BBC podcast ‘The Battersea Poltergeist’, treat yourself. Producer Danny Robins has a track record making entertaining, open-minded supernatural content. In ‘The Battersea Poltergeist’, he has artfully combined dramatic reconstructions with commentary to introduce us to a lesser-known British case from the 1950s.

Russell Hope Robbins’ 1959 classic ‘Encyclopedia of Witchcraft & Demonology’ lists the four key poltergeist indicators. They are: noises, knockings or footsteps; telekinesis; disappearance of small objects & their rediscovery later; and major disasters, such as arson.

Tick.

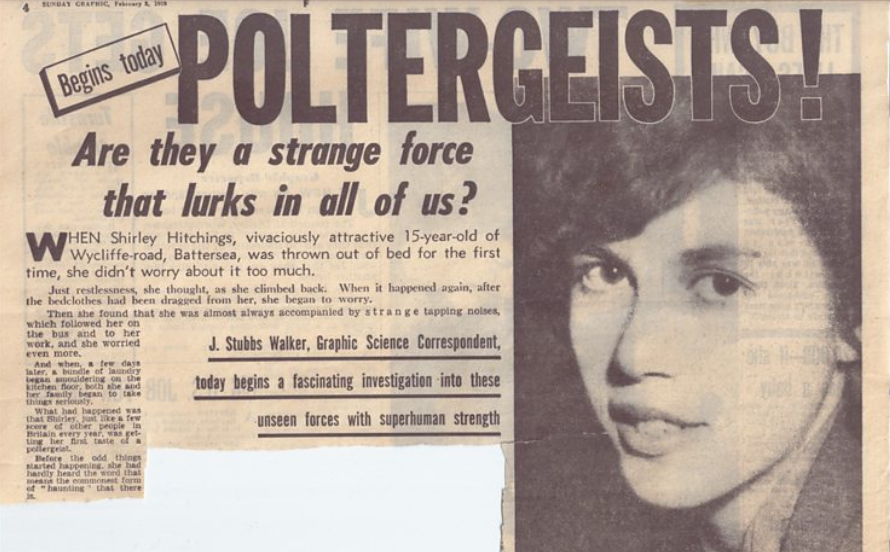

And this case conforms to another poltergeist standard, in that a very young woman was at the centre of the phenomena. Shirley Hitchings was the only girl in a working class family, living among her extended family in an emotional web that Robins does a very good job of dramatically reconstructing.

But there is another vital rôle in the social dynamic of poltergeist cases, one that is more easily overlooked.

Harold Chibbett (1900-1978), or ‘Chib’, was a psychic investigator. Chib had met such luminaries as Aleister Crowley in his lifelong search to understand occult phenomena. Perhaps more poignantly he had also met ghost-hunter Harry Price whose fame and success Chib hoped to replicate. If only he could find the right case …

Chib seems to have authentically believed in the Battersea poltergeist. He spent hours and nights at the house to recording events and became a close family friend. Unfortunately for him, Battersea did not enter the poltergeist Hall-of-Fame ‘til now, many years after his death. Even the 2013 book by Shirley Hitchings and James Clark ‘The Poltergeist Prince of London‘ didn’t make it as notorious as, for example, Enfield.

Chib seems to have authentically believed in the Battersea poltergeist. He spent hours and nights at the house to recording events and became a close family friend. Unfortunately for him, Battersea did not enter the poltergeist Hall-of-Fame ‘til now, many years after his death. Even the 2013 book by Shirley Hitchings and James Clark ‘The Poltergeist Prince of London‘ didn’t make it as notorious as, for example, Enfield.

Poltergeist cases usually start with young women who don’t have a lot of ‘clout’. However strange their stories, they need the momentum of a ‘facilitator’ to make the case known to a wider audience.

Facilitators come ready integrated into receptive networks; they can get plenty of traction with less effort. Facilitators have strong personal motives for their work. With many of them, Chib included I think, there is a genuine and strong desire to establish the fact of life after death.

Facilitators are usually more educated, at least on their favoured subject. Their knowledge of historical cases contributes to the participants’ ability to author an improvised ‘script’, with its inevitable escalation. Facilitators don’t just publicise the story; they provoke it with the attention they bring.

When you’re aware of the facilitator role you can identify them in historical poltergeist cases. We know about the 1663 ‘Drummer of Tedworth’ case not from the afflicted family, the Mompessons, but from the writings of a visiting clergyman Joseph Glanvill. He attributed the case to “some Daemon or Spirit” and wrote the case up in his 1681 ‘Saducisimus Triumphatus’. Glanvill was concerned that a new rationalism could remove God from the world: “… those that dare not bluntly say there is no God, content themselves … to deny there are spirits or witches”.

The Fox Sisters, whose playful pranks and raucous toe-cracking inadvertently precipitated the nineteenth century new religious movement of Spiritualism were too young and isolated to have started a career entirely by themselves. They were promoted by radical Quakers Amy and Isaac Post whose counter-cultural community provided the social heft that a couple of attention-seeking teenagers couldn’t

I’m a strong believer that the strange phenomena at Enfield would have disappeared if the psychic investigators Guy Playfair and Maurice Grosse had. Chib seemed to play the same avuncular rôle within the Hitchings family at Battersea.

The ‘facilitator’ dynamic can be seen in other allegedly supernatural contexts: the harm of other people’s social drama has been filtered and amplified by theologians, witch-hunters and self-appointed authorities for years. In the 1612 case of the Pendle witches, a local Justice of the Peace, Roger Nowell, sought to make a name for himself by investigating an stroke suffered by a pedlar. Two local families were implicated in witchcraft: one person died in prison and another ten survived to be hanged.

Even the case of the Cottingley Fairies needed a promoter. Creator of the world’s most evidence-led detective, Arthur Conan-Doyle, was a mystic who – like may of his generation – sought evidence of other planes of existence and life-after-death. He was gullible enough to fall for Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths fairy photos which are now known as the ‘Cottingley Fairies’.

I contributed to the ninth episode of the Battersea Poltergeist and touched on Chib’s role. Hope you enjoy. Throughout the series, the skeptical strand was very ably contributed by Dr. Ciarán O’Keeffe.

Reformation’s poster-boy Martin Luther (1483-1586) was one of the first to use the word ‘poltergeist’, which he listed as the fifth worst abuse of the Roman Catholic Church. He was a fervent man and a prolific writer, so we can only be grateful that he ran out of paper by the time he got to number one hundred and fourteen.

His meaning was that an institution and the men within it, an institution which had social heft and credibility, validated the belief in a probably-non-existent phenomenon because it could integrate this phenomenon into its worldview. Moreover, it had a remedy for it.

It’s a reminder that the creation of ghosts, poltergeists and gods is a social enterprise; each supernatural being needs attention to thrive. And the really successful memes are the ones with influential people behind them.