Uganda’s Child Sacrifices

Originally published January 2010

On Thursday night, the BBC brought us news of witchcraft and child-sacrifice in Uganda via two media: Radio 4’s ‘Crossing Continents’ and BBC2’s ‘Newsnight’ (19 mins to 33 mins) both carried reports by Tim Whewell.

In northern Uganda in the last year, police reckon there have been around two dozen ritual killings and 120 missing persons. People in the affected area and campaigners believe the numbers may be much higher, reflecting under-reporting to the police. So far, no-one has been prosecuted.

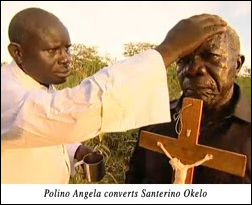

Whewall’s narrative followed the activities of a former child-sacrificing witchdoctor named Polino Angela who has spent the last twenty years attempting to move witchdoctors away from their murderous activities and to Christianity, in which time he claims to have made 2,400 converts.

Angela’s initiation happened in Kenya in what must have been 1968. A thirteen year old boy was slashed open so that he could be doused with his blood: the function of this was to bestow Angela with the commercial advantage of the ability to speak many languages (although English didn’t appear to be one of them).

Under instruction he went home to murder his own son, an action which made him: “… so hardened, I had no mercy for anybody”. During the years of his active career, he reckoned that he had been involved in the ritual demise of around seventy people while under the influence of a demon.

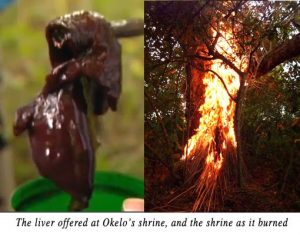

Angela was filmed visiting a witchdoctor named Santerino Okelo, whose shrine was eventually torched with its owner’s consent. Before the conflagration, the crew filmed the contents of the shrine, a tin of blood and a liver (of which provenance, it was impossible to say).

Angela was filmed visiting a witchdoctor named Santerino Okelo, whose shrine was eventually torched with its owner’s consent. Before the conflagration, the crew filmed the contents of the shrine, a tin of blood and a liver (of which provenance, it was impossible to say).

Okelo admitted that his customers captured other people’s children for sacrifice, usually while petitioning the spirits for wealth. The blame for the “ugly things” in which he had been involved was displaced from him, since the transaction was between the spirits and the customers: he was just a medium.

Okelo was bound by fear: fear of the people whose children had been taken, fear of the police if he confessed, but most of all fear of the spirits for abandoning them.

In northern Uganda, Peter Odongo showed us the grave of his three year old son who had been murdered a year ago. A post-mortem revealed that organs including the heart, liver and pancreas were missing from the boy’s corpse. He had also been slashed across the left hand. An eighteen month old girl named Robina had been found a few miles away with a slashed throat, and parents have understandably started taking their children everywhere with them for protection.

Later this year, some alleged witch doctors will be tried using the testimony of surviving victims, such as George Mukisa, whose penis was chopped off. George was found bleeding to death. Prompt action by surgeons saved his life, but his parents understandably despair for his future.

Shafik Kazike was seized in the street but the female witchdoctor to whom he was taken rejected him as an unsuitable sacrifice because he was circumcised. This is consistent with ritual sacrifice in other cultures that I know of: the god must always be given the ‘perfect’, the best. Parents are now circumcising their sons and piercing their daughters’ ears to make them ‘imperfect’.

In response to these deaths, in January 2009, the police set up the ‘Anti-Human Sacrifice and Human Trafficking Taskforce’. Assistant Commissioner Moses Binoga said that 2009’s twenty-six cases with a ritual element, were up from just three in 2007.

But why is there an increase now?

Assistant Commissioner Binoga echoed witchdoctor Santerino Okelo. It is: “ … caused by a desire for people to get wealth“

And Eunice Apio, the Director of FAPAD (Facilitation for Peace & Development) showed Nigerian Horror films to Whewell. It was not clear if the one they were watching were from Helen Ukpabio’s ‘Liberty Foundation Gospel Ministries’ execrable back-catalogue, but Apio confirmed:

“These movies …. are actually very popular, and not for the entertainment factor alone. The unemployed who are the majority of the youth … it comes with a message: you let blood … you get an easy route to wealth … people become desperate and they believe anything that is dangled before them”

It has been alleged that there are bodies under many of Kampala’s new buildings. This is a well-known magical practice called ‘foundation sacrifice’, whose intention is either to appease the local spirits into blessing your enterprise, or to bind the spirit of the person who you have killed to do the same job.

The fact is, as Whewell pointed out in his documentaries, Uganda is going through a period of severe social and economic dislocation, with a great deal of wealth to be had … by some. Just like Nigeria, it has an incredibly fractious political past and a hot modern economy which has, so far, not served all equally.

In addition, like Nigeria, it is a varied country by many criteria. There are two languages (Bantu in the south and Nilotic speakers in the north), two religions (Christians of different denominations make up about 84%, Muslims about 12 %).

In the north, the centre of the present concerns about human-sacrifice, the Lord’s Resistance Army has been involved in a long-running civil war with the Ugandan government. Their appalling human rights violations include the forcible recruitment of child soldiers.

Regular visitors will remember that I wrote and post on witch-hunting in Nigeria here.

Although that was witch-hunting (where there was probably no witchcraft) and this is witchcraft, I think that a lot of the observations still stand.

I’d like to restate my position from there, that belief in the supernatural is a necessary but not sufficient factor in large-scale witch-hunts and malign witchcraft. The key factors in social movements like these are religious, social and economic dislocation. It must be hard to see others thrive around you, to be shut out of the party and to be essentially impotent.

Witchcraft is a way of using force to claim your bit. With a worldview where religion, sorcery and science are essentially different parts of the same spectrum, it’s not so unusual.

It’s just that the stakes, potential rewards and therefore motivation have changed.

Even august governmental ministers such as James Buturo, Minister of Ethics & Integrity, declares a belief in spirits that doesn’t sit well on rationalist, secular ears:

“they do (exist) … we accept they do in every society mind you, but we don’t have to listen to them”

When the interviewer asked if it would be more helpful to deny the existence of the spirits, he replied:

“If we were to do that, that would be false because they are there anyway and people are not foolish … it’s as well we speak the truth about these matters … there is no merit that you can attach to these evil spirits, but they are there”

Disavowing the power of the supernatural and its power to the populace of Uganda would probably be a counter-productive intervention, I believe; the supernatural is a self-evident part of many people’s lives. In the short term, working within people’s belief systems will probably be more productive.

So although I found it a delicious irony was that an anti-human sacrifice ceremony was led by man solemnly carrying the logo of the largest human sacrifice cult the world has ever known, a cross, I can’t fault the tactics. Polino Angela seems a sincere Christian, and I think he stands ten times the chance of grafting people from one form of supernatural affiliation to another than trying to convert them immediately to atheism.

So although I found it a delicious irony was that an anti-human sacrifice ceremony was led by man solemnly carrying the logo of the largest human sacrifice cult the world has ever known, a cross, I can’t fault the tactics. Polino Angela seems a sincere Christian, and I think he stands ten times the chance of grafting people from one form of supernatural affiliation to another than trying to convert them immediately to atheism.

Personally, I wouldn’t worry about Minister Buturo’s beliefs. Many western leaders believe things every bit as peculiar out of context. It doesn’t necessarily mean that his campaign against magic will be insincere or ineffective.

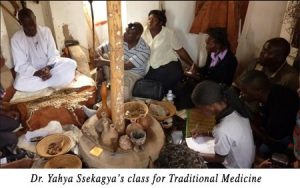

One approach to the problem explored by Whewell is to regulate traditional healers so that ‘imposters’ can be filtered out. At an outdoor academy for traditional healing, where students wear T-shirts with slogans like ‘traditional healers: we care’ and ‘stand up for children, reject child sacrifice’, tutor Dr. Yahya Ssekagya, said:

“One can pretend to be a healer and cheat the client … we have had spirits for many millenniums but there hasn’t been child sacrifice … we need to be recognised as a legal entity, then we will filter ourselves out”.

“One can pretend to be a healer and cheat the client … we have had spirits for many millenniums but there hasn’t been child sacrifice … we need to be recognised as a legal entity, then we will filter ourselves out”.

Dr Ssekagya’s qualifications are real – he’s a dentist – but I find his conviction that regulation will take care of the problem quaint at best and potentially dangerous at worst. Those who visit me regularly will know what I think of regulation in cases where the profession is anything other than potentially deadly (proven medicine and auto mechanics being two examples). It usually, IMHO, is a way of promoting the status of a trade, restricting practices, protecting a practising elite and driving fees up. Customer protection comes a few places down the list.

In addition, I think that the profession was/is probably regulated already. Admission and training were likely traditionally restricted by social connections and perhaps ability to pay for tuition. Very few societies had any professions worth a light which weren’t ‘managed’ in some way, or they would have become worthless. Dr Ssekagya’s proposed regulation is probably a more modern, ‘cerficated’ form of restriction with legal backing. Given that he appears to run an academy, I can see his incentive to campaign for his product to be restricted.

His comments suggest that he feels that the power of traditional medicine is real but ethically misdirected by rogue practitioners. When asked the difference between TM practitioners and witchdoctors, he says:

“Witchcraft was a western packaging of African science. A doctor can kill because he knows the medicine that kills but he can also secure life”

In other words, the intention is different but the power is the same.

Whether African traditional medicine provides results above placebo level, I don’t know (it would be hard to believe that generations of practitioners hadn’t left a legacy of surgical and herbal knowledge of some quality). But where there is a clear and strong financial incentive to use your ‘power’ for evil, a club with certificates is hardly likely to provide a compelling counter-force. This is especially true where the deployment of the law is so profoundly subject to irregularities and corruption. As one victim’s mother said in a heart-wrenching combination of plaintive and philosophical:

“I have nothing to do – that is our country”

Besides, there was evidence that witchcraft is already regulated by forces far stronger than a governmental statutory body.

The witchdoctor Santorino Okelo claimed to have seen clients, on average, three times per week and was paid 500,000 Ugandan shillings (£160/$265) each time. This is massive wealth in a country where most of the population live below the poverty line of $2 per day.

However, little of Santorino’s earnings were apparent in his surroundings: the explanation was that he had surrendered most of them to his ‘boss’. “I’m supposed to remain like a servant” he explained.

He was just part of a nationwide network which, it seems, is taxed at highly prejudicial levels by senior management. Asst. Commissioner Moses Binoga thinks that there are five or six witchdoctor protection rackets in the country. And where there are large sums of money and murderous activities, we can reasonably expect the management to be less than benign.

This is probably the single best place to target efforts in the short term – the higher, organised levels of the witch-doctor racket. But it would take a great deal of effort and involve tackling any corruption.

Dr. Ssekagya’s claim that child sacrifice is new should also be subject to some scrutiny.

I can agree that with social changes and the increased aspiration to wealth, the desire for strong magic and human sacrifice may have increased. However, Polino Angela gave up his ‘gruesome work’ twenty years ago and during his active twenty-two year career prior to that he claimed to have killed seventy or so people.

This means that human sacrifice was common enough in the seventies and eighties for one man to have a self-confessed river of blood on his hands, even if his claims are exaggerated. And the practice can hardly have been suddenly invented in 1968, when Angela was initiated.

While we’re on Angela’s figures, they do seem to me to be hyperbolous.

Angela claimed to have assisted in the demise of seventy human victims over twenty years: this is a reasonably modest 3.5 per year for a profession which has three clients a week (to judge by Santerino Okelo’s numbers). He also claims to have converted 2,400 witchdoctors in the last twenty years. That’s an average of 3.5 deaths per witchdoctor per year, and 120 converted witchdoctors per year since 1990.

That’s 8,400 lives saved per annum per practitioner after twenty years, or over the course of the twenty years, well over eighty thousand. Even if Angela’s converts were not as prolific as he, and worked at half the rate, it’s still over forty thousand. In a country of around thirty-two million, those are significant numbers. I’d be interested to see whether Uganda’s missing persons figures are commensurate.

I’m not denying that some Ugandan parents are going through hell right now, but I do think that the whole area could do with some sober statistics. I wonder, in fact, if Angela’s ‘2,400’ are converts to Christianity rather than active child-sacrificing witchdoctors.

Ultimately, it is to be hoped that a meritocracy will grow in Uganda, and that people will feel they can thrive by education and endeavour rather than witchcraft.

In the meantime, although I don’t think direct assault on supernatural world models will help, a sound scientific education, ideally in a secular institution, could be good over the long-term. The 70s and 80s were a bad time for education in Uganda, and the adult literacy rate was measured at 50% in 1990. This means that a huge swathe of the now-middle-aged population may lack the intellectual tools to dismantle a supernaturally-based worldview.

If you got a few quid going spare, I’d direct you to a page on the New Humanist website. The Mustard Seed School is a secular school based on humanist ideas of free inquiry, scepticism and rationalism. One of its mission statements is to:

“… demystify dogmatic and irrational ideologies based on religious fiction, fallacies, witchcraft, superstition”